The first national-level assessment of property buyouts in flood-prone areas, published today in Science Advances, reveals that buyouts funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) have taken place mostly in high-income, densely populated areas. Projections suggest that it is poor and rural areas, however, that would benefit most from a managed retreat from rising waters.

The study highlights a number of program management issues, including those concerning equity, that need to be addressed before scaling up property buyouts as part of a national strategy for managed retreat, the study’s authors said.

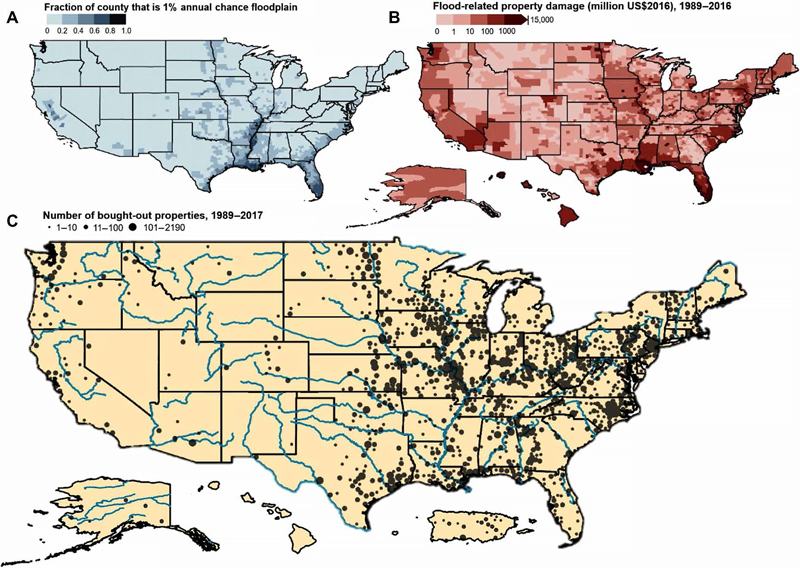

Where Buyouts Happen

“Here in the U.S. and virtually anywhere you look globally…development has placed people and assets in hazardous places,” lead researcher Katharine Mach told reporters at an 8 October press conference. A changing climate has led to more dangerous storms, more property damage, and more loss of life. “When it comes to weather and climate events we are now experiencing, we are unambiguously behind the eight ball.”

One way for society to adapt to climate change is through managed retreats from flood-prone areas.

“Retreat is moving people and assets out of hazardous places and taking that land and restoring it to open space,” said Mach, who researches climate change risk management at the University of Miami in Florida.

A floodplain will absorb more water than a parcel of developed land and can help manage flood risk. FEMA has administered the majority of U.S. funds for managed retreat for the past 30 years through its property buyout program.

The team gathered publicly available data on FEMA buyouts, flood maps, declarations of disaster, and the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. FEMA funded more than 43,000 buyouts of flood-prone properties between 1989 and 2017. Over the 30 years of the FEMA program, city- and county-level governments administered 94% of the buyouts across 49 states, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. (No buyouts took place in Hawaii.)

“We found out buyouts overwhelmingly take place in counties with higher flood risks,” said coauthor Carolien Kraan, a graduate student studying climate change adaptation at the University of Miami. “At the same time, however, not all counties that have high flood risk do buyouts.”

The three states with the highest property damage costs—Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi—had middling buyout numbers. This disparity might be caused by local choices about flood mitigation strategies and the prioritization of flood insurance subsidies over buyouts, the team speculated.

Inequities in Administering Buyouts

What made a flood-prone county more likely to administer buyouts?

“We found the counties that have administered buyouts, on average, have higher income and population density,” Kraan said. Population density and income level were used as proxies for a county’s administrative capacity.

“However, when we looked within those counties to where the buyouts took place, the neighborhoods where the buyouts were actually located, on average, have lower household income, lower population density, and more racial diversity,” Kraan added. High-buyout areas also corresponded to areas with lower levels of education and English language proficiency.

These trends raise concerns about equity. Do the programs enable white people to move into less diverse areas? Are people of color, those with less formal education, or those with a lower proficiency in English relocated in the same numbers and in the same ways as less marginalized groups?

Case-based analyses and an independent investigation conducted by NPR earlier this year have shown that “after a disaster, rich people get richer and poor people get poorer. And federal disaster spending appears to exacerbate that wealth inequality.”

Cases have also shown that vulnerable populations have been pressured into buyouts, lied to about flood risk, and relocated to equally flood-prone areas.

The FEMA data do not include demographic or personal information about buyout participants, so researchers could not assess whether the property buyouts augmented large-scale systemic inequalities, widened the wealth gap, or increased neighborhood segregation.

Property buyouts are long, arduous, and complicated processes, so the trend might simply reflect county-level resources. “Buyouts require resources and capacity to administer, and not all governments may be equally able to access the program,” Kraan said. “While it isn’t clear why buyouts are taking place in more vulnerable neighborhoods, the study points to the importance of evaluating equity in buyout practices and outcomes.”

Concerns for Scaling Up

The data also revealed that more and more counties each year buy out only a couple of properties. Small buyouts are less cost-effective than larger buyouts, can have a higher administrative burden, and could miss opportunities for more strategic planning of floodplains. Understanding why buyouts have been small can help us scale up for future retreat efforts, the team wrote.

Regardless, if buyouts are left to local governments to administer, “future retreat in poorer and more rural communities may be less likely to be supported and managed by government. These populations could therefore be at increased risk of becoming trapped in areas of high flood risk,” the team wrote.

Another concern is the gaps in FEMA records of property buyouts. “Fifty percent of the fields are blank when it comes to what types of structures and what types of residences they are,” Mach said. “We know they are mostly single-family homes that are primary residences. But then if you go to the address-level data…it seems like, for example, mobile home park residences may particularly be falling through the cracks.”

The data gaps add a new layer to the equity questions raised here, she added, and hinder our ability to learn from the buyouts to date and to inform future large-scale deployments.

“It’s not a ‘retreat or else’ type of question,” Mach said. “It’s about how retreat fits into our broader portfolio for climate change adaptation.”

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer